Original Title: The Importance of Full-Stack Openness and Verifiability Author: Vitalik Buterin, Founder of Ethereum; Translated by Golden Finance Perhaps the biggest trend of this century so far can be summed up by the phrase "the internet has become real life." It began with email and instant messaging. For millennia, private human communication took place with mouth, ear, pen, and paper; now it relies on digital infrastructure. Then came digital finance—both crypto-finance and the digitization of traditional finance itself. And then there's our health: Thanks to smartphones, personal health-tracking watches, and data inferred from purchasing behavior, all sorts of information about our bodies is being processed by computers and computer networks. Over the next twenty years, I expect this trend to extend to a wide range of other areas, including various government processes (eventually including voting), monitoring of physical and biological indicators and threats in public environments, and ultimately, through brain-computer interfaces, even our own minds. I believe these trends are inevitable; the benefits they offer are simply too great, and in a highly competitive global environment, civilizations that reject these technologies will be the first to lose, while those that embrace them will gain an advantage. However, in addition to their enormous benefits, these technologies also profoundly affect power dynamics within and between nations. The civilizations that will benefit most from the new technological wave are not those that consume it, but those that create it. Centrally planned equal access schemes can only provide a fraction of the benefits of closed platforms and application programming interfaces, and they will fail beyond a pre-defined "normal." Moreover, this future requires a significant degree of trust in technology. If this trust is broken (e.g., by the presence of backdoors or security vulnerabilities), it can cause serious problems. Even the mere possibility of such a breach can force a reversion to fundamentally exclusionary models of social trust ("Did someone I trust make this?"). This creates an incentive structure that permeates the entire technology stack: those who have the power to make decisions are sovereign. Avoiding these problems requires two intertwined qualities across the entire technology stack (including software, hardware, and biotechnology): true openness (i.e., open source, including free licensing) and verifiability (ideally, including direct verification by end users).

The Importance of Openness and Verifiability in Health

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw the consequences of unequal access to production technologies. Vaccines are produced in only a few countries, resulting in huge differences in the timing of vaccine availability. Developed countries received high-quality vaccines in 2021, while other countries received lower-quality vaccines in 2022 or 2023. Although there are some initiatives to ensure equal access to vaccines, their effectiveness is limited because vaccine designs rely on capital-intensive, proprietary production processes that can only be performed in a few places. The second major problem with vaccines is the opacity of their science and communication strategies, which attempt to conceal any risks or drawbacks from the public. This is inconsistent with the facts and has ultimately greatly exacerbated public distrust. This distrust has now evolved into a near-rejection of the results of half a century of scientific research. In fact, both of these problems are solvable. Vaccines like PopVax, funded by Barvi, are cheaper to develop and have more transparent R&D and production processes, reducing inequalities in access and making their safety and effectiveness easier to analyze and validate. We can take a step further in vaccine design by prioritizing verifiability. Similar issues exist in the digital realm of biotechnology. When you talk to longevity researchers, one of the first common refrains you'll hear is that the future of anti-aging medicine is personalized and data-driven. To know which medications and nutritional changes to recommend to patients today, you need to understand their current physical condition. This is far more effective if large amounts of data can be digitally collected and processed in real time. The same concept applies to defensive biotechnology aimed at preventing adverse effects, such as combating epidemics. The sooner an epidemic is detected, the more likely it is to be stopped at its source—and even if that's not possible, every extra week buys more time to prepare and begin developing countermeasures. During an epidemic, knowing where people are sick in real time is invaluable for deploying a response. If the average person infected with an epidemic learns about their illness and self-isolates within an hour of becoming ill, the virus will spread 72 times more slowly than if they infect others within three days. If we know that 20% of locations are responsible for 80% of transmission, improving air quality in those locations could yield further benefits. All of this requires (i) a large number of sensors, and (ii) sensors that can communicate in real time to feed information to other systems. If we go even further in the “science fiction” direction, we’ll encounter brain-computer interface technology, which could improve productivity, help people better understand each other through telepathy, and open a safer path to highly intelligent AI. If the bio- and health-tracking infrastructure (both personal and spatial) is proprietary, then the data falls by default into the hands of large corporations. These companies have the ability to build applications on top of it, while others cannot. They might be able to provide data through API access, but API access would be restricted, used to extract monopolistic fees, and potentially revoked at any time. This means that only a select few individuals and companies have access to the most crucial elements of 21st-century technology, which in turn limits who can profit financially from it. On the other hand, if this personal health data isn't secure, hackers could use it to blackmail you for any health issue, manipulate insurance and healthcare prices, and exploit you. If this data includes location tracking, they could even know where to abduct you. Your location data (often hacked) could, in turn, be used to infer your health. If your brain-computer interface is hacked, it means hostile forces are reading (or worse, tampering with) your thoughts. This is no longer science fiction. In short, this offers enormous benefits, but also significant risks: risks that a strong focus on openness and verifiability is well-suited to mitigating. The Importance of Openness and Verifiability in Personal and Commercial Digital Technologies Earlier this month, I needed to fill out and sign a form for a legal matter. I was out of the country at the time. While there was a national electronic signature system, I didn't have it installed. I had to print the form, sign it, walk to a nearby DHL courier, spend a considerable amount of time filling out the paper form, and then pay to have it shipped halfway around the world. Time: half an hour, cost: $119. That same day, I needed to sign a (digital) transaction on the Ethereum blockchain to perform an action. Time: 5 seconds, cost: $0.10 (To be fair, without blockchain, signing would be completely free). Stories like these are ubiquitous in areas such as corporate and nonprofit governance, intellectual property management, and more. You can find them in the funding proposals of a significant number of blockchain startups over the past decade. Beyond that, there are the most quintessential use cases for "digitally exercising individual power": payments and finance. Of course, all of this carries significant risk: what if the software or hardware is hacked? The cryptocurrency community recognized this risk early on: blockchains are permissionless and decentralized, so if you lose access to your funds, there are no recourse. No keys, no coins. Consequently, the cryptocurrency community has long considered multi-signature and social recovery wallets, as well as hardware wallets. However, in reality, the lack of a trustworthy "uncle in the sky" in many cases isn't an ideological choice; it's an inherent part of the landscape. In fact, even in traditional finance, "uncle in the sky" can't protect most people: for example, only 4% of fraud victims recover their losses. In use cases involving the custody of personal data, recovering from a data breach is impossible, even in theory. Therefore, true verifiability and security are needed—both in software and hardware. A technique for checking whether a computer chip is manufactured correctly. Importantly, when it comes to hardware, the risks we're trying to protect against go far beyond questions like "Is the manufacturer evil?" The problem is that there are a large number of dependencies, most of which are closed source, and any one of them could lead to unacceptable security consequences. This article presents some recent examples of how microarchitectural choices can undermine the side-channel attack resistance of designs that are provably secure in a software-only model. Attacks like EUCLEAK rely on vulnerabilities that are harder to detect because many components are proprietary. AI models can be backdoored during training if trained on compromised hardware. Another issue in all of these cases is that even if closed and centralized systems are absolutely secure, they still have drawbacks. Centralization creates persistent leverage between individuals, companies, or nations: if your core infrastructure is built and maintained by a potentially untrustworthy company in a potentially untrustworthy country, you're vulnerable to pressure. This is precisely the problem that cryptocurrencies were designed to solve—but these problems exist far beyond finance. The Importance of Openness and Verifiability in Digital Citizenship Technologies I frequently speak with people from all walks of life who are trying to figure out better forms of government that are more suited to the diverse national contexts of the 21st century. Some seek to take existing political systems to the next level, empowering local open source communities and using mechanisms like citizen assemblies, lotteries, and quadratic voting. Others, like economists working on land value taxes or congestion pricing, seek to improve their countries' economies. Different people may have varying degrees of enthusiasm for each idea. But they all have one thing in common: they all require high-bandwidth participation, so any realistic implementation must be digital. Basic things like pen and paper keeping track of who owns what and holding elections every four years are fine, but anything that requires higher bandwidth or more frequent consultations is a no-go. Historically, however, security researchers have treated ideas like electronic voting with a range of skepticism to hostility. Here's a good summary of the case against electronic voting. Quoting from the document:

First, this technology is "black box software," meaning the public cannot access the software that controls the voting machines. While companies protect their software to prevent fraud (and crack down on competitors), this leaves the public in the dark about how voting software works. Companies can easily manipulate the software to produce fraudulent results. Furthermore, the vendors who sell these machines compete with each other and cannot guarantee that the machines they produce are in the best interest of voters and guarantee the accuracy of ballots.

There are many real-world examples that justify this skepticism. These arguments hold true in a variety of other contexts. But I predict that as technology advances, the "let's just not do it" response will become increasingly impractical in many areas. The world is rapidly becoming more efficient because of technology (for better or worse), and I predict that any system that doesn't follow this trend will become increasingly irrelevant as people circumvent it. So we need an alternative: actually doing the hard work and figuring out how to make complex technical solutions secure and verifiable. In theory, "secure and verifiable" and "open source" are two different things. It's definitely possible to be both proprietary and secure in some areas: airplanes are highly proprietary technology, but overall, commercial aviation is a very safe way to travel. But what a proprietary model can't achieve is secure consensus—the ability to gain the trust of mutually distrustful participants. Civic institutions like elections are one example of where secure consensus is crucial. Another is evidence collection in court. Recently, in Massachusetts, evidence from a high-volume breathalyzer test was ruled invalid because information about a malfunctioning test was discovered to have been withheld. The article is quoted below:

Wait, so all the results were wrong? No. In fact, the breathalyzer results in most of the cases had no calibration problems. However, because investigators later discovered that the state crime lab had withheld evidence, suggesting that the problem was more widespread than they had stated, Judge Frank Gaziano wrote that the due process rights of all these defendants had been violated.

Due process in court is inherently an area that requires not only fairness and accuracy but also a consensus on what fairness and accuracy are—because without a consensus that courts are doing the right thing, society can easily devolve into a situation where people act on their own.

Beyond verifiability, openness itself has inherent advantages. Openness allows local groups to design systems for governance, identity, and other needs in ways that are compatible with local goals. If voting systems are proprietary, a country (or province or town) that wants to try a new one faces a much greater difficulty: they either have to convince companies to implement their preferred rules as a feature, or they have to start from scratch and do all the work to make it secure. This adds to the high cost of innovation in political systems.

In any of these areas, a greater focus on the open source hacker ethic would give more autonomy to local implementers, whether they are individuals, part of a government, or a corporation. To do this, open build tools need to be widely available, and the infrastructure and code base need to be freely licensed to allow others to build on it. Copyleft licenses are particularly important to minimize power differentials. Another important area of civic technology in the coming years will be physical security. Unfortunately, I predict that the recent rise of drone warfare will make "no high-tech security" an untenable option. Even if a country's laws don't infringe on personal freedoms, they're meaningless if that country can't protect you from other countries (or unscrupulous companies or individuals) imposing their laws on you. Drones make such attacks much easier. Therefore, we need to take countermeasures, which will likely involve a large number of counter-drone systems, sensors, and cameras. If these tools are proprietary, data collection will be opaque and centralized. If they are open and verifiable, we have a chance to find a better approach: security devices could be proven to output only limited amounts of data under limited circumstances and delete the rest. We could have a digital, physical security future that acts more like a digital guard dog than a digital panopticon. We could imagine a world where public surveillance devices are required to be open and verifiable, allowing anyone to legally select a random surveillance device in public, disassemble it, and verify its authenticity. University computer science clubs could regularly engage in this educational activity. We cannot avoid the deep embedding of digital computers in every aspect of our lives (both individual and collective). By default, we're likely to end up with digital computers built and run by centralized corporations, optimized for the profit motives of a few, backdoored by their governments, and with most of the world unable to participate in their creation or know if they're secure. But we can try to find better alternatives.

Imagine a world where:

you have a secure personal electronic device—one with the power of a phone, the security of a cryptographic hardware wallet, and the inspectability not quite like a mechanical watch, but very close.

your messaging apps are encrypted, your messaging patterns are obfuscated via a mix network, and all your code is formally verified. You can rest assured that your private communications are truly private. Your finances are standardized ERC20 assets on-chain (or on a server that publishes hashes and proofs to the chain to guarantee their correctness), managed in a wallet controlled by your personal device. If you lose your device, it can be recovered through another device of your choice, or through the devices of family, friends, or institutions (not necessarily governments: if anyone can easily do it, a church, for example). Open-source versions of infrastructure similar to Starlink already exist, so we can have robust global connectivity without relying on a few individual players.

The open LLM on your device scans your activity, provides suggestions and automatically completes tasks, and warns you when you may be acquiring incorrect information or are about to make a mistake.

The operating system is also open source and formally verified.

You are wearing a 24/7 personal health tracking device that is also open source and auditable, allowing you to access your data and ensure that no one else has access to it without your consent. We have more advanced forms of governance that use lotteries, citizen assemblies, quadratic voting, and often clever combinations of democratic voting to set goals, and some method of filtering opinions from experts to determine how to achieve them. As a participant, you can be confident that the system is enforcing the rules as you understand them. Public spaces are equipped with monitoring devices that track biological variables (such as carbon dioxide and air quality index levels, the presence of airborne diseases, and wastewater). However, these devices (as well as any surveillance cameras and defense drones) are open source and verifiable, and there are legal systems through which the public can randomly inspect them.

This world will be more secure, free, and allow for more equal participation in the global economy than it is today. But achieving this world will require significant investment in a variety of technologies:

Advanced forms of cryptography. What I call the "God of Cryptography"—ZK-SNARKs, or fully homomorphic encryption and obfuscation—are so powerful because they allow you to perform arbitrary computations on data with multiple parties and guarantee the output while keeping both the data and the computation private. This enables more robust privacy-preserving applications. Cryptography-related tools—for example, blockchains can provide strong guarantees for applications, ensuring that data cannot be tampered with and users cannot be excluded; differential privacy techniques can add noise to data to further protect privacy—are also applicable here.

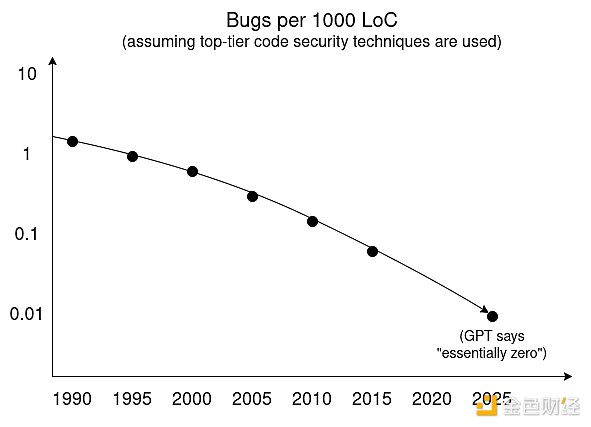

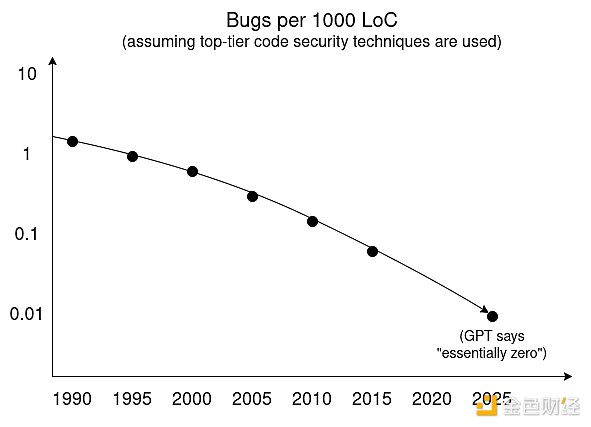

Application and user-level security. An application is secure only if the security guarantees it provides can be truly understood and verified by users. This will require software frameworks that make it easy to build applications with strong security properties. Importantly, it will also require browsers, operating systems, and other middleware (such as locally running observers, such as LLMs) to each play their part in validating applications, determining their risk level, and presenting this information to users. Formal verification. We can use automated proof methods to algorithmically verify that a program satisfies properties of interest, such as non-data leakage or vulnerability to unauthorized third-party modification. Lean has recently become a popular formal verification language. These techniques have begun to be used to verify ZK-SNARK proofs for the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) and other high-value, high-stakes cryptographic use cases, and are finding wider application. Beyond this, further progress is needed on other more common security practices.

The cybersecurity fatalism of the 2000s was wrong: vulnerabilities (and backdoors) can be overcome. We *just* need to learn to prioritize security over other competing goals.

Open source and security-focused operating systems More and more such operating systems are emerging: GrapheneOS as a secure version of Android, streamlined security kernels like Asterinas, and Huawei's HarmonyOS (its open-source version) are using formal verification (as long as it's open, anyone can verify it, it doesn't matter who produced it. This is a great example of how openness and verifiability can combat global division). Secure, open-source hardware security. If you can't ensure that the hardware actually runs the software and isn't independently leaking data, then no software is secure. In this regard, I'm most interested in two short-term goals: Personal secure electronic devices—blockchain people call them "hardware wallets," open-source enthusiasts call them "secure phones," but once you understand the need for security and universal access, the two will eventually converge into the same thing. Physical infrastructure in public spaces—smart locks, the biometric monitoring devices I mentioned above, and general "internet of things" technology. We need to be able to trust them. This requires open source and verifiability. A secure and open toolchain for building open-source hardware. Today, hardware designs rely on a series of closed-source dependencies. This significantly increases the cost of hardware manufacturing and makes the entire process more license-dependent. This also makes hardware verification impractical: if the tools that generate chip designs are closed-source, you don't know what to verify. Even existing tools, like scan chains, are often unusable in practice because so many of the necessary tools are closed-source. This can all change. Hardware verification (e.g., infrared and X-ray scanning). We need methods to scan chips to verify that they actually contain the intended logic and are free of unnecessary components, preventing accidental tampering and data extraction. This can be done destructively: auditors randomly order products containing computer chips (using identities that appear to be ordinary end users), then disassemble the chips and verify that the logic matches. Using infrared or X-ray scanning, this can be done non-destructively, potentially scanning every chip. To achieve a consensus of trust, we ideally need hardware-based authentication technology that is readily accessible to the public. Today's X-ray machines don't yet meet this standard. This situation can be improved in two ways. First, we can improve authentication devices (and the authentication-friendliness of chips) to make them more accessible to the public. Second, we can supplement "full authentication" with more limited forms of authentication, even on smartphones (such as ID tags and key signatures generated by physically unclonable functions), to verify stricter claims, such as "Is this machine from a batch produced by a known manufacturer, and a random sample of that batch is known to have been thoroughly verified by a third party?" Open-source, low-cost, localized environmental and biological monitoring devices. Communities and individuals should be able to measure themselves and their environment and identify biological risks. This includes a variety of technologies: personal medical devices (such as OpenWater), air quality sensors, general airborne disease sensors (such as Varro), and larger-scale environmental monitoring devices.

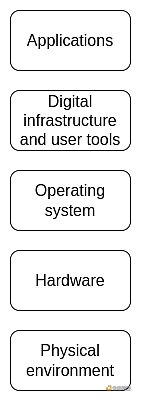

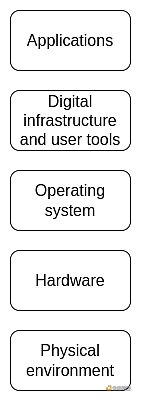

Openness and verifiability at every layer of the stack are important

From Here to There

A key difference between this vision and more “traditional” visions of technology is that it is more friendly to local sovereignty, individual empowerment, and freedom. Security is achieved not by searching the entire world and ensuring there are no bad actors anywhere, but by making the world more robust at every level. Open means openly building and improving every layer of technology, not just centrally curated open-access API programs. Verification isn't the preserve of proprietary stamp-stamping auditors (who are likely in cahoots with the companies and governments that roll it out)—it's a right of the people and a socially encouraged hobby. I believe this vision is more powerful and more aligned with our fragmented 21st-century global landscape. But we don't have infinite time to execute it. Centralized security approaches, including more centralized data collection and backdoors, and reducing verification to simply "was this made by a trustworthy developer or manufacturer," are rapidly gaining momentum. Attempts to replace true open access with centralized approaches have been going on for decades. This attempt may have begun with Facebook's internet.org and will continue, each more complex than the last. We need to act quickly to compete with these approaches and demonstrate publicly to the public and institutions that better solutions are possible.

If we can successfully realize this vision, one way to understand the world we’ll be in is that it’s a kind of retro-futurism. On the one hand, we’ll benefit from more powerful technologies that allow us to improve our health, organize ourselves more efficiently and resiliently, and protect us from threats old and new. On the other hand, the world we’ll get will have restored some of the characteristics that people took for granted in 1900: infrastructure that people can freely disassemble, verify, and modify to suit their needs; anyone can participate, not just as a consumer or an “app developer,” but at any level of the stack; and anyone can be confident that a device will do what it claims to do. Designing for verifiability comes at a cost: many hardware and software optimizations provide much-needed speed improvements at the expense of designs that are more difficult to predict or more brittle. Open source makes it harder to profit under many standard business models. I believe both of these issues are overblown—but convincing the world won't happen overnight. This raises the question: what are the pragmatic goals we should pursue in the short term?

I'll propose a solution: work to build a completely open source and easily verifiable stack for high-security, low-performance applications—whether consumer or institutional, remote or in-person. This will cover hardware, software, and biometrics.

Most computations that truly need security don't usually need speed, and even when speed is needed, there are often ways to combine high-performance but untrustworthy components with trusted but low-performance components to achieve high levels of performance and trust for many applications.

achieving the highest security and openness for everything is unrealistic. But we can start by making sure these features are available where they really matter. Anais

Anais