Author: Luca Prosperi Translator: Deep Tide TechFlow

When I graduated from university and applied for my first management consulting job, I did what many ambitious but cowardly male graduates often do: choose a firm that specializes in serving financial institutions.

In 2006, banking was a symbol of "cool." Banks were typically located in the grandest buildings in the most beautiful neighborhoods of Western Europe, and I was looking forward to using that opportunity to travel. However, no one told me that this job came with a more secretive and complex condition: I would be "married off" to one of the world's largest but also most specialized industries—banking—indefinitely. The need for banking experts has never disappeared. During economic expansions, banks become more innovative, and they need capital; during economic contractions, banks need restructuring, and they still need capital. I tried to escape this vortex, but like any symbiotic relationship, getting out of it is much harder than it seems.

Capital Retention Buffer (CCB): Increase CET1 by 2.5%Countercyclical Capital Buffer (CCyB): Increase by 0–2.5% depending on macroeconomic conditions

Global Systemically Important Bank Surcharge (G-SIB Surcharge): Increase systemically important banks by 1–3.5%

In effect, this means that under normal Pillar I conditions, large banks must maintain a CET1 of 7–12%+ and total capital of 10–15%+. However, regulators do not stop at Pillar I. They also implement stress testing regimes and, when necessary, add additional capital requirements (i.e., Pillar II).

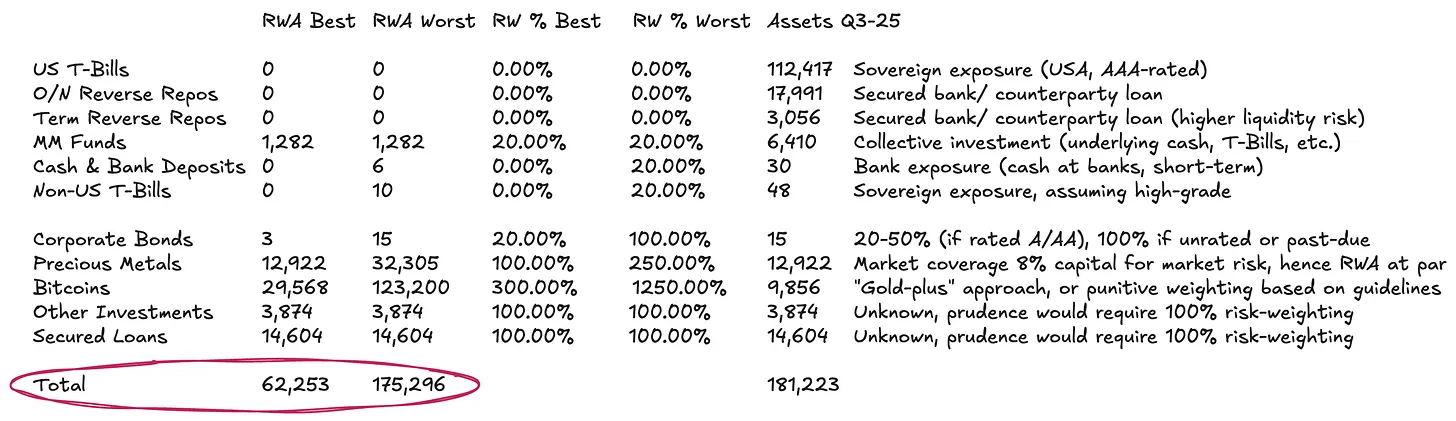

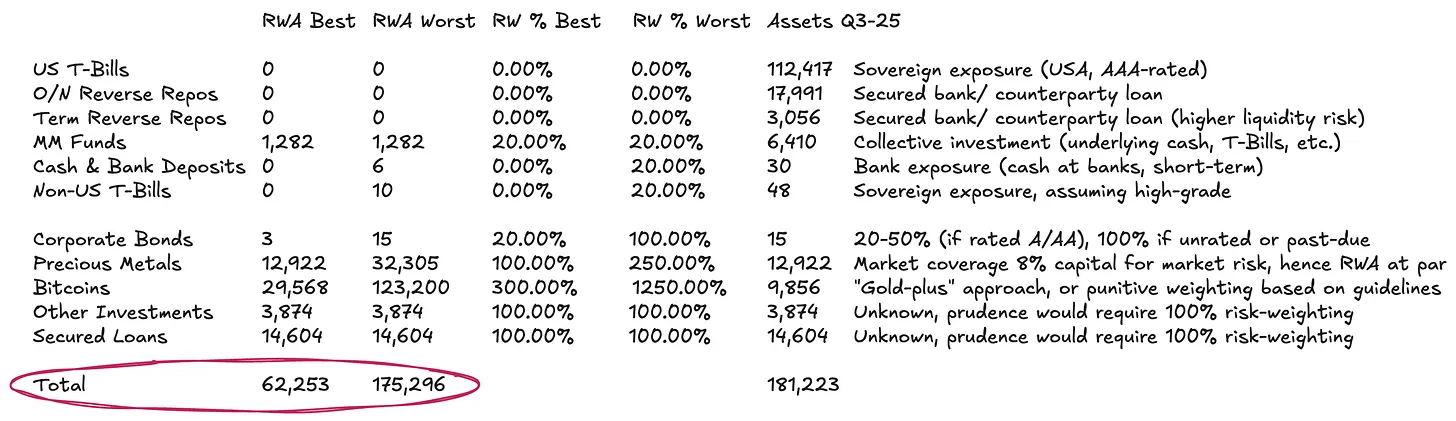

Risk-weighted classification (3), loan ledger is completely opaque. For loan portfolios, the transparency is almost zero. Since information such as borrowers, maturity dates, or collateral is unavailable, the only reasonable option is to apply a 100% risk weight. Even so, this is still a relatively loose assumption given the complete lack of any credit information. Based on the above assumptions, for Tether (USDT), with total assets of approximately US$181.2 billion, its risk-weighted assets (RWAs) could range from approximately US$62.3 billion to US$175.3 billion, depending on how its commodity portfolio is treated.

Tether's Capital Situation

Now, we can put the last piece of the puzzle in and examine Tether's equity or excess reserves from the perspective of relative risk-weighted assets (RWAs). In other words, we need to calculate Tether's Total Capital Ratio (TCR) and compare it with regulatory minimums and market practices. This step of the analysis inevitably carries a certain degree of subjectivity.

Therefore, my goal is not to draw a definitive conclusion on whether Tether has sufficient capital to reassure $USDT holders, but rather to provide a framework to help readers break down this issue into easily understandable parts and form their own assessment in the absence of a formal prudential regulatory framework. Assuming Tether's excess reserves are approximately $6.8 billion, its Total Capital Adequacy Ratio (TCR) will fluctuate between 10.89% and 3.87%, depending primarily on how we treat its $BTC exposure and how conservative we are about price volatility. In my view, while fully reserving $BTC aligns with the most stringent Basel interpretation, it seems overly conservative. A more reasonable baseline assumption is holding sufficient capital buffers to withstand $BTC price volatility of 30%-50%, a range well within the historical fluctuation range. Under the aforementioned baseline assumptions, Tether's collateral level generally meets the minimum regulatory requirements. However, compared to market benchmarks (such as well-capitalized large banks), its performance is less satisfactory. By these higher standards, Tether might require an additional approximately $4.5 billion in capital to maintain its current $USDT issuance. With a more stringent, fully punitive approach to $BTC, the capital shortfall could be between $12.5 billion and $25 billion. I believe this requirement is overly demanding and ultimately does not meet practical needs. Independent vs. Group: Tether's Rebuttals and Controversies

Tether's standard rebuttal on the collateral issue is that, from a group perspective, it has a large amount of retained earnings as a buffer. These figures are indeed impressive: as of the end of 2024, Tether reported annual net profits exceeding $13 billion, and its group equity exceeded $20 billion. The more recent third-quarter audit for 2025 shows that its year-to-date profit has exceeded $10 billion.

However, a counter-rebuttal to this is that, strictly speaking, these figures cannot be considered as the regulated capital of $USDT holders.

These retained earnings (located on the liabilities side) and proprietary investments (located on the assets side) are both at the group level and outside the segregated reserves. While Tether has the capacity to allocate these funds to the issuing entity in the event of problems, it has no legal obligation to do so. This liability segregation arrangement gives management the option to inject capital into the token business if necessary, but it does not constitute a hard commitment. Therefore, viewing the group's retained earnings as capital fully available to absorb $USDT losses is an overly optimistic assumption. A rigorous assessment requires examining the group's balance sheet, including its holdings in renewable energy projects, Bitcoin mining, artificial intelligence and data infrastructure, peer-to-peer telecommunications, education, land, and gold mining and concession companies. The performance and liquidity of these risky assets, and whether Tether is willing to sacrifice them to protect token holders in times of crisis, will determine the fair value of its equity buffer. If you're expecting a definitive answer, I'm sorry to say you might be disappointed. But that's precisely Dirt Roads' style: the journey itself is the greatest reward.

Aaron

Aaron

Aaron

Aaron Catherine

Catherine Snake

Snake Clement

Clement Davin

Davin Kikyo

Kikyo Clement

Clement Hui Xin

Hui Xin Jasper

Jasper Catherine

Catherine