Author: Charlie Liu

Last Wednesday, Nvidia's highly anticipated earnings call brought encouraging results, finally relieving the anxiety of countless investors: revenue grew by over 60% year-over-year, the data center business sold out, and guidance was revised upwards again.

However, the capital market reacted differently. Nvidia's stock price briefly surged before falling back, and a wider range of AI concept stocks collectively declined, widening credit spreads for companies aggressively expanding AI infrastructure. The open market even experienced a 2.5% plunge in just over an hour.

Recently, talk of an "AI bubble" has been rampant: MIT claims that 95% of enterprise AI pilot projects have failed to generate measurable returns on investment, central bank governors warn that valuations are as distorted as they were in the late 1990s, and the media has begun to delve into the cyclical revenues among major AI companies. In other words, despite high revenue figures, the market has begun to doubt whether the underlying structure of the entire industry can support these valuations. The Real Bottleneck of AI: Electricity and Capital Recently, Goldman Sachs, in an energy and power industry report, made an interesting analogy, comparing the current situation to two historical infrastructure supercycles. Nineteenth-century railway construction spurred the development of modern investment banks and bonds as a popular asset class. The development of the internet at the end of the 20th century fostered venture capital and fueled the rise of high-risk growth stocks and IPOs. In the current AI era, traditional stocks and bonds cannot meet the demands brought about by the explosive growth in electricity and computing power. We need a new model of capital formation, or even a new capital market. Moreover, the fundamental constraint lies in our ability to provide sufficient AI-level power and finance it without overwhelming the financial system. The Power Dilemma: Over the past two decades, the average annual growth rate of the US power grid has been less than 1%—enough to cope with the era of web servers and smartphones, but a disaster for AI factories. Analysis shows that to meet the combined demands of new data centers, electric vehicles, and industrial reshoring, the US now needs to add approximately 80 gigawatts of generating capacity annually. However, the actual annual increase is only 50-60 gigawatts, creating a shortfall of about 20 gigawatts annually—enough to support two or three cities the size of New York City. The first instinctive options for filling this gap are always more natural gas power plants, accelerated wind, solar, and energy storage deployment, and the anticipated resurgence of nuclear power. But none of these can meet demand in a reasonable timeframe: Building new natural gas power plants is tempting on paper, but in reality, it has become an average four-year project, with turbine supply bottlenecks extending equipment delivery cycles to three to five years, not including approvals and grid connection queues. Onshore wind power, including preliminary planning and grid connection studies, typically takes three to four years, and can even drag on for nearly a decade, although the actual construction phase only takes six to twenty-four months. Utility-grade solar power is more modular and faster to build, with a typical construction cycle of 12-18 months. The average development cycle for battery storage is less than two years, therefore "PV + storage" accounts for more than 80% of the expected new installed capacity in the US by 2025. Nuclear power, especially small modular reactors (SMRs), may be the most compelling long-term answer to 24/7 AI-level electricity, but the first wave of SMR projects in North America is expected to reach commercial operation around 2030-2035. All these options are essential, but in a world where grid connection queues often have waiting times of four to seven years, they are only medium- to long-term solutions. The only way to significantly accelerate this process is to reuse existing sites with land, high-capacity grid connections, and power infrastructure—especially large Bitcoin mining farms. In practice, upgrading existing mining farms to AI facilities requires only a few months of modification work (liquid cooling, power distribution, GPUs), rather than the four to seven years required to apply for new grid connections from scratch. This is precisely why AI companies acquire or partner with mining companies: CoreWeave's bid for CoreScientific was primarily aimed at converting its approximately 1.3 gigawatts of mining infrastructure to AI. Although the impressive performance of Gemini 3 has led to speculation that TPUs might replace GPUs in the future, thus reducing power demand, the growing consensus in the market remains that GPUs will be the primary driver, with TPUs playing a secondary role. Just like the GPU demand concerns raised by the sudden emergence of DeepSeek, Nvidia's GPUs have once again withstood the pressure, and the expected power demand remains strong. Capital Dilemma Since ChatGPT ignited the AI craze in late 2022, demand for AI data centers has surged, and financing models have evolved through several phases. The first phase was almost entirely supported by the operating cash flow of hyperscale enterprises. When you generate hundreds of billions of dollars in free cash flow annually, you can quietly build massive amounts of data centers and lock up huge amounts of GPUs. But the scale of the current vision—a multi-trillion dollar AI stack globally—has begun to put pressure on these balance sheets. Thus, we entered the second phase: debt and private credit. Investment-grade borrowing has surged to fund AI construction; high-yield issuers (Bitcoin miners transitioning to AI, new data center developers) have entered the junk bond market; and the rapidly growing private credit system has added custom loans, sale-leasebacks, and revenue-sharing facilities. It's worth noting that much of this funding never appears on the balance sheet as simple "debt," but rather as off-balance-sheet **private credit**: these exist in project joint ventures, structured leases, and other off-balance-sheet instruments, transforming capital expenditures into long-term obligations and making the entire stack more like shadow financing. If the trillion-dollar AI capital expenditure projections are roughly accurate, banks and bondholders will not be enough to support it; by 2028, private credit and these quasi-invisible structures are expected to provide a significant share—perhaps the majority—of the capital behind AI data centers and power transactions. Even so, it's still not enough, so we're seeing early signs of a **third phase: securitization**. Asset-backed securities for data center rents and leases have quietly grown to approximately $80 billion in outstanding value and are projected to reach approximately $115 billion by 2026. On the equity side, REIT-like instruments and joint ventures are splitting the economic interests of "land + shell + power vs. GPU vs. AI application revenue." The public credit market has taken note of these potential risks. Bloomberg's criticism of Meta's $27 billion off-balance-sheet data center joint venture's "creative financing," and its commentary on Oracle's aggressive lease-and-borrow strategy, both point to the same thing: tech giants cannot fully fund their AI initiatives, and every new financing trick they employ makes bond investors more nervous. So, is this an AI bubble? To some extent—but not in the way headlines suggest. On the equity front, valuations are indeed staggering. AI-related companies have captured an excessive share of market gains, the S&P 500 is trading at valuation multiples reminiscent of the internet age, and Nvidia's market capitalization briefly exceeded the GDP of almost every country except the US and China. But equity investors at least believe they know how to price growth and hype. The more interesting—and more dangerous—movement lies in the **capital stack** behind all this. The problem isn't that AI has no practical uses, but that we're trying to finance a generation of infrastructure construction with tools and intermediaries not designed for this specific risk portfolio (long-term physical risks: power plants, grid upgrades; short-term technological risks: old GPUs may become obsolete within five years). Returning to the historical analogy mentioned earlier: railroads weren't simply financed by general loans for crude oil; the need for funds for thousands of miles of tracks and rolling stock gave rise to modern investment banks and standardized railroad bonds. The internet wasn't simply grafted onto corporate balance sheets; it fostered venture capital partnerships and norms surrounding equity-backed portfolios of loss-making companies due to extremely asymmetric returns and appreciation potential. Therefore, the real question is: in the AI era, what should be a more effective capital formation mechanism? And what are its native financial instruments? RWA: A Financial Instrument for the New Era On the surface, Wall Street seems to have found the answer. "RWA" has become a buzzword in earnings calls and regulatory speeches. It's a general term for tokenized government bonds, stocks, bank deposits, and on-chain buyback experiments, considered the financial market infrastructure of the new era. According to the SEC's narrative, it seems inherently the financial infrastructure of the AI era, like railroad bonds for steel or startup equity for the internet. However, in essence, tokenized RWA itself is not a new form of capital; it's merely a new packaging for familiar financial products: behind it are still senior and mezzanine debt; common and preferred stock; revenue-sharing agreements, etc. In the context of energy or data centers, this could mean tokenized shares of 20-year power purchase agreements; tokenized project equity with on-chain waterfall logic; tokenized REIT units; or short-term overcollateralized notes backed by contract GPU revenue. So, if RWA isn't anything new, what real advantages does it offer beyond the hype and hype compared to traditional financial instruments? Through analysis of some early-stage projects, we can see four practical benefits: **Fine Divisibility:** A $50 million project share can be divided into thousands of on-chain positions, allowing position sizes to match broader investment requirements. Global Reach: As long as securities rules are followed, the same instrument can be held by funds, family offices, DAOs, or corporations in different jurisdictions without having to rewire the underlying infrastructure each time. Programmable Cash Flow Allocation: Smart contracts can hold stablecoins, enforce cascade flows and contracts, and automatically pay coupons or revenue shares based on verifiable performance data, without relying on spreadsheets and intermediaries. Fast Settlement Based on USD Stablecoins: You can transfer principal and interest across time zones and weekends in minutes, although secondary market depth is still far thinner than traditional bond markets. All of this sounds like a financial upgrade, but it still doesn't seem to answer the deeper questions of capital formation. In the railway era, bonds were effective because of the system surrounding them that transformed steel and land into standardized securities; in the internet era, high-growth equity was effective because venture capital partnerships could transform chaotic startups into lucrative conduits. But tokenized RWA cannot miraculously create that flywheel out of thin air. The real financial challenge of the AI+energy cycle isn't how leading AI companies can continue to "smartly" use financial engineering to borrow money to build AI data centers and power plants, but rather how to initiate, aggregate, and mitigate the risks of thousands of small, distributed assets (solar roofs, batteries, micro-data centers, flexible loads) and express their cash flows in a way that allows global capital to hold them with genuine confidence. This is precisely the gap that DePIN RWA attempts to fill, and why, in this context, energy and computing networks are more important than another generic "RWA narrative." Energy DePIN: The Formation of Long-Tail Capital

This is precisely where DePIN—the idea of using tokens to coordinate the deployment of physical infrastructure—becomes interesting.

Currently, DePIN is still small. Messari's 2024 report shows that the entire sector has approximately 350 tokens with a total market capitalization of about $50 billion, trading at about 100 times their combined revenue. Specifically, the Energy DePIN sub-category has about 65 projects with a total market capitalization of less than $500 million.

If you are a traditional infrastructure investor, these numbers are laughable compared to the trillion-dollar AI capital expenditure plans. But the best-designed form of Energy DePIN almost perfectly matches the power bottleneck that the AI stack is encountering.

Take Daylight as an example.

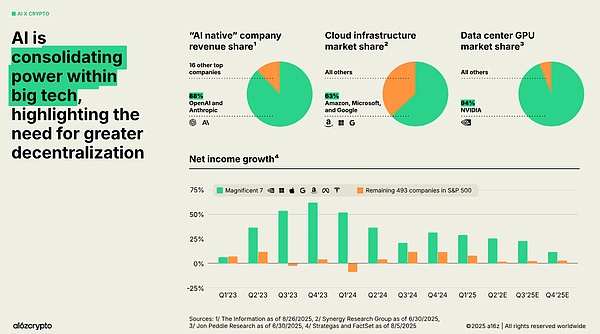

Its core logic is that distributed energy resources—rooftop solar, home batteries, EV charging stations—can be coordinated into a software-defined power plant if they can detect and pay for “flexible” capacity, rather than just raw power generation. Its “flexible proof” mechanism pays with $GRID tokens when smart devices commit to adjusting their consumption or charging/discharging behavior during future high-voltage periods; energy companies burn $GRID to purchase access to that flexible capacity. Based on this, $GRID, as an energy-backed currency, touches every part of the stack: installation discounts for homeowners; payments for data and analytics; staking and derivatives for regional capacity mispricing; and insurance for off-chain capacity commitments. In its US-only model, the total volume across physical and financial energy markets is approximately $1 trillion annually. Daylight's model is tightly coupled with the existing power grid. This is a key selling point if you believe AI data centers will primarily be located within or near the current transmission grid, and utilities are willing to pay high prices for flexibility. If grid connection delays and regulations slow everything down, that's also a risk. In contrast, there's Arkreen. If Daylight is "grid-native, US-centric," then Arkreen is "grid-agnostic, globally oriented." It connects distributed renewable energy resources to a Web3-enabled network of data and assets. Participants install "mining rigs" or connect via API; the network records verifiable green energy generation data and tokenizes it into renewable energy certificates and other green assets. Arkreen has connected over 200,000 renewable energy data nodes, issued over 100 million kilowatt-hours of tokenized REC, and facilitated thousands of on-chain climate actions. Its vision is clearly globalization and long-tail: a peer-to-peer energy asset trading network where households and small producers can connect their DERs to the DePIN system, earn tokens through "influence-based" activities, and indirectly form virtual power plants or green AI offsets. Individually, none of these projects can fund the next gigawatt data park for hyperscale enterprises. But they point to a possible form of "capital formation" in the AI era—if we stop considering only nine-figure project funding blocks and start thinking in atomic-level "kilowatt-hours." This is precisely the centralization concern pointed out in the crypto + AI narrative and the latest a16z crypto state report: laissez-faire AI tends to be centralized—large models, large clusters, large clouds. In contrast, blockchain excels at aggregating large numbers of small, distributed contributions and giving them fluid global market access.

A Cryptographic Bridge Connecting Kilowatt-Hours and AI Tokens

Currently, the value chain from marginal "kilowatt-hours" to "AI tokens" is fragmented.

Power plants sign PPAs with utility companies; utility companies or developers sign contracts with data centers; data centers sign contracts with cloud providers and AI companies; AI companies sell API usage rights or seats; somewhere at the top of the stack, users pay a few dollars to run an inference test.

Each link is independently financed, with different investors, risk models, and jurisdictional constraints. The opportunity, and a crypto-native version of "capital formation," lies in making this chain transparent and programmable.

On the supply side, you can tokenize kilowatt-hour-related output, representing a claim to specific renewable energy generation currents; tokenize RECs and carbon credits; and tokenize flexible capacity commitments from batteries, smart devices, and VPPs. Projects like Arkreen have demonstrated that this is technically and commercially feasible at a reasonable scale. In the midstream, you can express infrastructure as tokenized RWAs: equity and debt in data centers, grid connection upgrades, off-meter generation and storage, and GPU clusters. Here, traditional securitization still occurs, but on-chain tracks make it more transparent: investors know exactly which assets back tiered products when purchasing them, and cash flows are settled in stablecoins that move in minutes rather than days. On the demand side, you can link energy and computing with AI-native tools: GPU-hour tokens, inference second credits, and even application-layer "AI service" tokens. As agent AI systems mature, some of these tokens will be held and spent directly by software agents—programs capable of assessing where to purchase computing and electricity at the margin and dynamically arbitrage between providers. Thus, every marginal kilowatt-hour used by an AI model, from its origin (rooftop, solar power plant, nuclear SMR) to its consumption in a GPU rack and its monetization in AI applications, is **traceable, priced, and hedged**. This doesn't require each link to be on the same chain or denominated in the same token. Rather, it means that the state of each link is machine-readable and can be stitched together by smart contracts and agents. If this is achieved, you are essentially creating a new form of capital: any investor, anywhere, can choose where on this chain to take risk—energy, power grids, data centers, GPUs, AI applications—and purchase tokenized exposure of the appropriate size and duration. The balance sheets of hyperscale enterprises won't disappear, but they will no longer be the only way to store that risk. Conclusion This story is not a foregone conclusion. The combination of "large companies + large capital" is sufficient to accomplish all of this independently. Hyperscale enterprises may decide to directly own the energy stack through vertical integration and keep cash flow internal. Long-tail energy DePIN may never surpass centralized projects. Even if only a small fraction of AI-related energy and computing resources are ultimately financed and coordinated through DePIN and tokenized RWA, we have already answered the open questions left by Goldman Sachs and a16z's call for decentralization. At this moment, computing power and electricity are intertwined in unprecedented ways, and the form of capital is quietly being reshaped.

Hui Xin

Hui Xin

Hui Xin

Hui Xin Alex

Alex Aaron

Aaron Davin

Davin Aaron

Aaron Aaron

Aaron Jixu

Jixu Jasper

Jasper Clement

Clement Catherine

Catherine