Golden Web3.0 Daily | Japan Reorganizes Web3 and Cryptocurrency Policy Department

Golden Finance launches Golden Web3.0 Daily to provide you with the latest and fastest news on games, DeFi, DAO, NFT and Metaverse industries.

JinseFinance

JinseFinance

For ease of reading, this article is published in two parts, the upper and lower parts. This article is the upper part.

Asset Tokenization: A New Financial Paradigm in the Web3.0 Era

Finance is essentially the temporal allocation of resources in an uncertain environment. As Bodie and Morton (2000) put it, "Finance is the study of how people allocate resources over time in uncertain environments." They point out that financial decisions differ from other resource allocation decisions because the costs and benefits of financial decisions are distributed over time, and no one can know the outcomes in advance. In the real world, the vast majority of financial decisions depend on the financial system, which includes financial institutions, financial markets, and financial regulatory authorities. So, how can we judge the efficiency of the financial system in allocating resources over time? Arrow and Debreu's general equilibrium model (1954) provides a concise and powerful explanation: under conditions of perfect competition, a complete market encompassing all future states must have an equilibrium price system that allows resource allocation to reach Pareto optimality. A "complete market" is one in which, for the space of future states, there exist sufficiently many atomic securities—called "Arrow-Debreu securities"—that are state-dependent (payments are triggered by a certain future state), mutually exclusive (no correlation between different states), and complete (covering all future states) so that the payment stream for any future state can be realized through a linear combination of these securities. A simple example can illustrate the relationship between Arrow-Debreu securities and complete markets. Suppose today (t=0) there are two economic entities: a vendor who needs to set up a stall tomorrow (t=1) and an umbrella seller who wants to sell umbrellas tomorrow. Tomorrow's state space consists of two states: rain and no rain. Suppose there are two Arrow-Debreu securities in the market: a "rain security" that pays a certain amount if it rains tomorrow; and a "no rain security" that pays a certain amount if it does not rain tomorrow. Since tomorrow's state space contains two mutually exclusive states (rain and no rain), the market also has two mutually exclusive and complete securities. This makes the financial market a complete market. A vendor can buy a "rain" security to hedge losses from rain, and an umbrella seller can buy a "no rain" security to hedge losses from no rain. All economic entities are hedged against future losses—this is optimal risk sharing. At the same time, vendors and umbrella sellers can freely engage in today's production activities (such as preparing ingredients for tomorrow's stall) and consumption activities (such as enjoying a feast in anticipation of tomorrow's profits) without worrying about the impact of tomorrow's weather. This is known as the "Fisher Separation Theorem." Of course, to achieve a complete market, the number of atomic securities must scale with the state space. If the number of states increases and the state space expands, Arrow-Debreu securities will need to be further refined and increased in number. For example, if the state of "raining tomorrow" were to become "light rain," "moderate rain," or "heavy rain," and the state of "no rain tomorrow" were to become "cloudy," "overcast," or "sunny," six corresponding Arrow-Debreu securities would be needed to form a complete market. Complete markets obviously don't exist in reality. This is because the real world is plagued by numerous transaction costs, making it impossible to create an atomic security for every state. Any financial instrument (stocks, bonds, loans, derivatives, etc.) is a contract, and transaction costs are incurred throughout the entire process from contract signing to contract completion (Yin Jianfeng, 2006): Before signing, economic parties need to gather information (information search costs) and, in an environment of asymmetric information, identify counterparties (identification costs); contract signing requires repeated negotiations (negotiation costs); after signing, in an environment of asymmetric information, monitoring of counterparty compliance is necessary (supervision costs); upon contract expiration, verification of the actual state is necessary (verification costs); and finally, payment and settlement based on the state is required (payment and settlement costs). Although perfect markets do not exist, humanity has been continuously moving toward this ideal through various financial innovations, dating back to the Sumerians in 5000 BC (Goetzmann and Loewenhorst, 2010). The wave of financial liberalization that began in the United States in the 1980s greatly accelerated the pace toward perfect markets, leading to the emergence of a large number of new underlying securities (such as over-the-counter Nasdaq stocks and junk bonds) and derivatives (options, futures, swaps, etc.). Among these various financial innovations, securitization, which integrates numerous underlying securities and derivatives, is the epitome. Simply put, securitization involves packaging and dividing previously untradable, non-standardized financial instruments (such as mortgages) into smaller, standardized, tradable securities. Similar to asset securitization, the recently emerging asset tokenization (also known as "tokenization") packages and segments various cryptoassets and real-world assets (RWAs) into tokens (also known as "tokens") that are denominated, stored, and traded on a blockchain. Compared to asset securitization, due to the programmability, composability, divisibility, and atomic settlement of tokens, asset tokenization is infinitely closer to creating various atomic Arrow-Debreu securities, making it a more significant financial innovation towards complete markets. Of course, looking back at thousands of years of human financial innovation, every move towards complete markets, depending on the scale of the progress, can initially trigger varying degrees of financial risk, or even financial crises. For example, the rapid development of the British stock market in the early 18th century led to the first stock market crisis in human history—the South Sea Bubble of 1720. The emergence of money market funds in the 1980s exacerbated disintermediation in the US banking industry, leading to the bankruptcy of numerous banks. Asset securitization evolved into a massive wave of structured finance in the early 2000s, laying the groundwork for the 2007 US subprime mortgage crisis and the subsequent global financial crisis. In short, the greater the extent to which financial innovation moves toward a complete market, the more necessary it is to have supporting financial regulatory measures and risk management plans in its initial stages.

The following article will first discuss the mechanism of asset securitization and structured finance and the resulting global financial crisis in 2008, which can provide useful insights for the emerging asset tokenization; Section 3 takes Web3.0 as the background to analyze the types of asset tokenization, basic processes and the prospects of decentralized finance based on this; Just like asset securitization back then, asset tokenization is still far from mature. How to improve financial supervision and prevent the risks of tokenization is the main content of Section 4; The article ends with our basic judgment: If human beings will eventually enter an era in which the real physical world and the virtual digital world are closely integrated, then in this era, as the "core of the modern economy", finance must naturally also achieve a close integration of reality and virtuality.

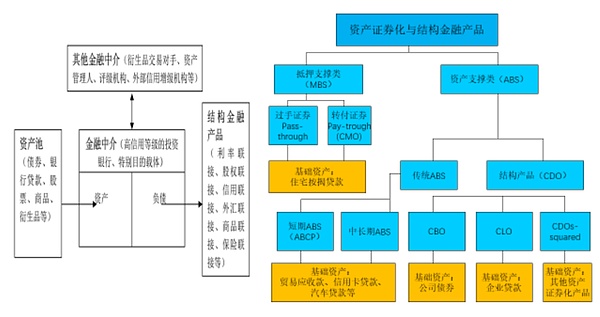

In today's financial system, asset securitization and the structured finance evolved on this basis have become common financial technologies that have been widely used. By overcoming real-world transaction costs, these technologies created state-dependent securities that previously didn't exist, bringing liquidity to previously untradable financial instruments. However, these technologies also introduced new transaction costs—particularly the costs of identifying the quality of underlying assets and the costs of overseeing the behavior of financial intermediaries. At a time when regulation severely lagged behind innovation, these new costs laid the groundwork for the financial crisis. (I) Asset Securitization Asset securitization has a long history. As early as 1852 and 1899, France and Germany enacted laws related to the transfer of housing loans. In Germany, mortgage-backed bonds (MBBs) issued under the Mortgage Bank Act—known as "Pfandbriefe" in German—can be considered the earliest securitized products. In 1938, the US government invested $10 million to establish the first government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mac), which began actively exploring and cultivating the secondary market for residential mortgages. In 1970, the second GSE, Freddie Mac, was established. That same year, the first mortgage-backed security (MBS) was issued. The true takeoff of asset securitization began in the 1980s, fueled by a series of financial liberalization reforms that expanded the space for future states. As with the earlier examples of street vendors and umbrella vendors, the rapid growth of asset securitization was driven by the needs of two types of economic entities. The first was banking institutions, which faced interest rate and liquidity risks. Before interest rate liberalization, thanks to the protection of Regulation Q of the Banking Act of 1933, banks could issue long-term, fixed-rate loans and create short-term, fixed-rate deposits, earning a stable interest rate spread. After interest rate liberalization, demand deposit rates on banks' liabilities began to fluctuate, increasing interest rate risk. More importantly, demand deposits began to flow to emerging non-bank financial institutions, particularly money market funds, putting banks under immense disintermediation pressure and urgently needing to address asset liquidity issues. The second category is newly emerging institutional investors, particularly pension funds, which have proliferated following pension system reform. These institutions need to allocate long-term, relatively safe fixed-income securities, but the non-standardized nature of mortgages makes them difficult to access. Against this backdrop, the MBS market began to expand. Initially, MBS were intended to address the liquidity issues of mortgages. The two GSEs were the primary buyers and securitizers of these loans, with the underlying assets being confirming loans or prime mortgages, whose credit risk was strictly controlled. This type of loan has three key characteristics: First, the borrower must have complete proof of income and an excellent credit score (above 620 points); second, there are strict requirements for the payment-to-income (PTI) ratio and the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, with PTI and LTV capped at 55% and 85%, respectively; and third, the interest rate is fixed and remains unchanged for the duration of the contract. Furthermore, these loans must also have additional credit enhancements, such as insurance company guarantees. Because the sole purpose of asset securitization is to generate liquidity, the design of MBSs is very simple: Fannie Mae and Foley purchase loans from banks to form an initial pool of assets. They then establish a securitization conduit, a special purpose vehicle (SPV), to transfer all interests in the initial assets to the SPV, achieving a true sale and bankruptcy remoteness. Finally, the SPV issues homogeneous securities with the same amount, risk, and return. Under this issuance method, the cash flows from the original asset pool are simply distributed equally to each investor without any changes. The SPV serves merely as a vehicle for transferring asset rights and interests, without any other function. Therefore, this type of security is called a pass-through security. (II) Structured Finance Since the 1990s, with the development of the financial derivatives market, a completely new financial model based on securitization technology—structured finance—has emerged. Structured finance is a financial activity centered on financial intermediaries such as investment banks (Yin Jianfeng, 2006). The process includes three steps: first, pooling, in which financial intermediaries package the original assets into an asset pool; second, de-linking, which is usually achieved through real sales and bankruptcy isolation through special purpose vehicles (SPVs), so that the income and value of the underlying assets are not affected by the behavior of the original equity holders and intermediaries; third, structuring, which restructures the risk and return characteristics of the asset pool according to investors' preferences, thereby forming new securities, namely structured finance products.

Figure 1 Structured Finance and Products

Structured finance is a continuation of asset securitization, but there are significant differences from traditional asset securitization: First, the financial instruments being securitized are no longer limited to compliant residential mortgage loans with low credit risk and only liquidity issues, but can also include any other assets - it can even be said that everything can be securitized; Second, the role of financial intermediaries is no longer to passively package and divide assets into simple standardized securities, but to become active securities designers and asset managers; Third, based on the attributes of the packaged assets and the design of the structure by the financial intermediaries, the resulting structured finance products can be a variety of complex and sophisticated securities related to interest rates, equity, credit, etc. One area where structured finance has been widely used is in the US subprime mortgage market. Subprime mortgages have been around since the 1960s, but they weren't called that back then. Instead, they were referred to as "non-confirming loans." "Non-confirming" refers to loans that don't meet Fannie Mae and Foley's purchasing requirements. These loans have three key characteristics: First, the borrowers' creditworthiness is poor, primarily low-income minorities. These borrowers typically lack credit history and income verification, with credit scores below 620. Second, their PTI and LTV exceed 55% and 85%, respectively. Not only do borrowers' incomes fall far short of the principal and interest owed, but many also require down payments of less than 20% or even zero. Third, over 85% of subprime loans have floating interest rates, and their overall debt burden is significantly higher than that of prime loans. To ease the initial repayment burden, loan repayments are structured as follows: first, low monthly payments are typically required for the first two years of the loan, followed by a "reset" after which the interest rate is significantly increased to match the market rate. For example, some subprime mortgages allow borrowers to repay the loan at a fixed rate below market interest for the first two years, before converting to a floating rate loan with an interest rate above market interest. Some subprime mortgages allow borrowers to repay only interest initially, or even allow for negative amortization (where the repayment amount is less than the current interest required to repay the loan). Figure 2: The General Structure of Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). Unlike the securitization of legitimate loans, which only requires addressing liquidity, the securitization of subprime loans requires addressing the high credit risk inherent in them. Otherwise, pension funds, life insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds with lower risk appetites would avoid participating in this market. A structured finance product fulfills this task: CDOs (Collateralized Debt Obligations). While there are numerous types of CDOs, their structures are generally similar (Figure 2). First, subprime loans were packaged and injected into an asset pool, then bankruptcy-removeable and sold through an SIV (structured investment vehicle)—a similar but more proactive securitization channel to an SPV. The resulting securities, ranked from lowest to highest in terms of credit risk and investment returns, were senior securities, intermediate securities, subordinated securities, and equity securities. If the underlying assets defaulted, the losses would be borne first by investors in the equity securities, followed by investors in the subordinated securities, and so on. This tiered structured design thus separated high-risk, homogeneous subprime loans into securities tailored to investors with varying risk appetites. Furthermore, CDOs could hedge credit risk through credit derivatives or utilize external credit enhancement agencies. Through this combination of measures, senior securities typically achieved credit ratings close to those of Treasury bonds, making them a popular investment target for domestic US institutional investors and foreign sovereign wealth funds. (III) Financial Crisis: Subprime mortgages emerged in the 1960s, but their scale remained relatively small. With the widespread adoption of structured finance products, primarily CDOs, subprime mortgages also spread. Since GSEs primarily issue MBS securitization products, while non-GSEs primarily issue structured finance products, including CDOs, a comparison of their scale reveals market changes (Figure 3). Figure 3: Proportion of various types of institutional assets in the total assets of U.S. financial institutions (%) Note: “GSE” refers to the proportion of securitized products issued by GSEs; “Non-GSE” refers to the proportion of securitized products issued by institutions other than GSEs. Data source: U.S. Flow of Funds Statement. In 1980, the proportion of non-GSE securitized products was smaller than that of GSE securitized products. By 1990, the former had grown to more than twice the size of the latter, and by the time the subprime mortgage crisis erupted in 2007, it was three times the size. As structured finance gained popularity, banks' business models also shifted: from a "loan-and-hold" model to a "loan-and-distribute" model, where loans are immediately packaged and sold to the market through securitization. As a result, the proportion of bank assets in total financial institutions' assets declined significantly (Figure 3): in 1980, bank assets accounted for over 40%, but by 2000, it had fallen to 20%. The continued evolution of structured finance ultimately triggered the US subprime mortgage crisis in 2007, which escalated into the global financial crisis after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in October 2008. In hindsight, the outbreak of the crisis was not surprising at all, as the three potential risks associated with financial innovation had always existed. First, the product's structural design ignored systemic risk. The diversification of credit risk through structural design, such as tranching, was premised on the assumption that credit risk stemmed solely from the idiosyncratic risks of individual subprime borrowers, rather than from the systemic risk caused by a simultaneous decline in housing prices nationwide. If housing prices fell simultaneously nationwide, all subprime loans would face default, and even investors in senior securities would be unable to avoid losses. Second, the moral hazard of financial intermediaries, including lending banks, rating agencies, and investment banks, was ignored. Under the "loan-and-distribute" model, lending banks transfer loan risks to securities investors, bearing only minimal risk. Consequently, they are more inclined to issue high-interest, high-risk subprime loans. Furthermore, after issuing loans, they are less likely to monitor borrowers' behavior, leading to the increasingly poor quality of the underlying securitized assets. The three major credit rating agencies also share this tendency. To reap the rewards of credit ratings, they generally tend to give higher ratings to structured products like CDOs. Investment banks, exemplified by Lehman Brothers, pursued profits from high leverage, even deliberately concealing the poor quality of the underlying assets from investors. They designed increasingly complex product structures, amplifying leverage through complex structures and allowing risks to spread rapidly across financial institutions, amplifying them into a financial crisis. Finally, there is a lack of oversight. Asset securitization and structured finance span not only traditional banking and securities businesses, but also the financial systems of various countries. However, before 2008, the US regulatory model was characterized by multiple regulators and separate sectors, making it impossible to effectively monitor the accumulation and contagion of cross-market risks. Furthermore, regulatory agencies across various countries lacked close international regulatory cooperation, making it impossible to prevent the cross-contagion of country risks or provide unified liquidity support after a crisis.

Golden Finance launches Golden Web3.0 Daily to provide you with the latest and fastest news on games, DeFi, DAO, NFT and Metaverse industries.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceGolden Finance launches Golden Web3.0 Daily to provide you with the latest and fastest news on games, DeFi, DAO, NFT and Metaverse industries.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceWeb3, the third generation of the Internet, is a decentralized network architecture built on blockchain technology.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceGolden Finance launches Golden Web3.0 Daily to provide you with the latest and fastest news on games, DeFi, DAO, NFT and Metaverse industries.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceThrough statistics and analysis of security incidents in the Web3.0 field over the past year, the latest trends in Web3.0 security are fully revealed.

JinseFinance

JinseFinanceA recent study by CoinGecko has shed light on the harsh reality facing Web3 games, revealing that a substantial 70% of games launched in 2023 have faced failure.

Aaron

AaronMetatrust and Scantist are joining forces to host an event on 31 October 2023 at Bybit's office.

Olive

OliveEveryone would agree that the world is becoming increasingly digitized, with the aptly named ‘Web 3.0’ era seemingly just around ...

Bitcoinist

Bitcoinist Nulltx

Nulltx Cointelegraph

Cointelegraph